Sustainable packaging: navigating bio-based PET, rPET and EPR compliance in the beverage sector

A panel at Drinktec India 2025 examined the meaning of sustainability and the practical realities of meeting India’s regulatory expectations

18 Nov 2025 | By Sai Deepthi P

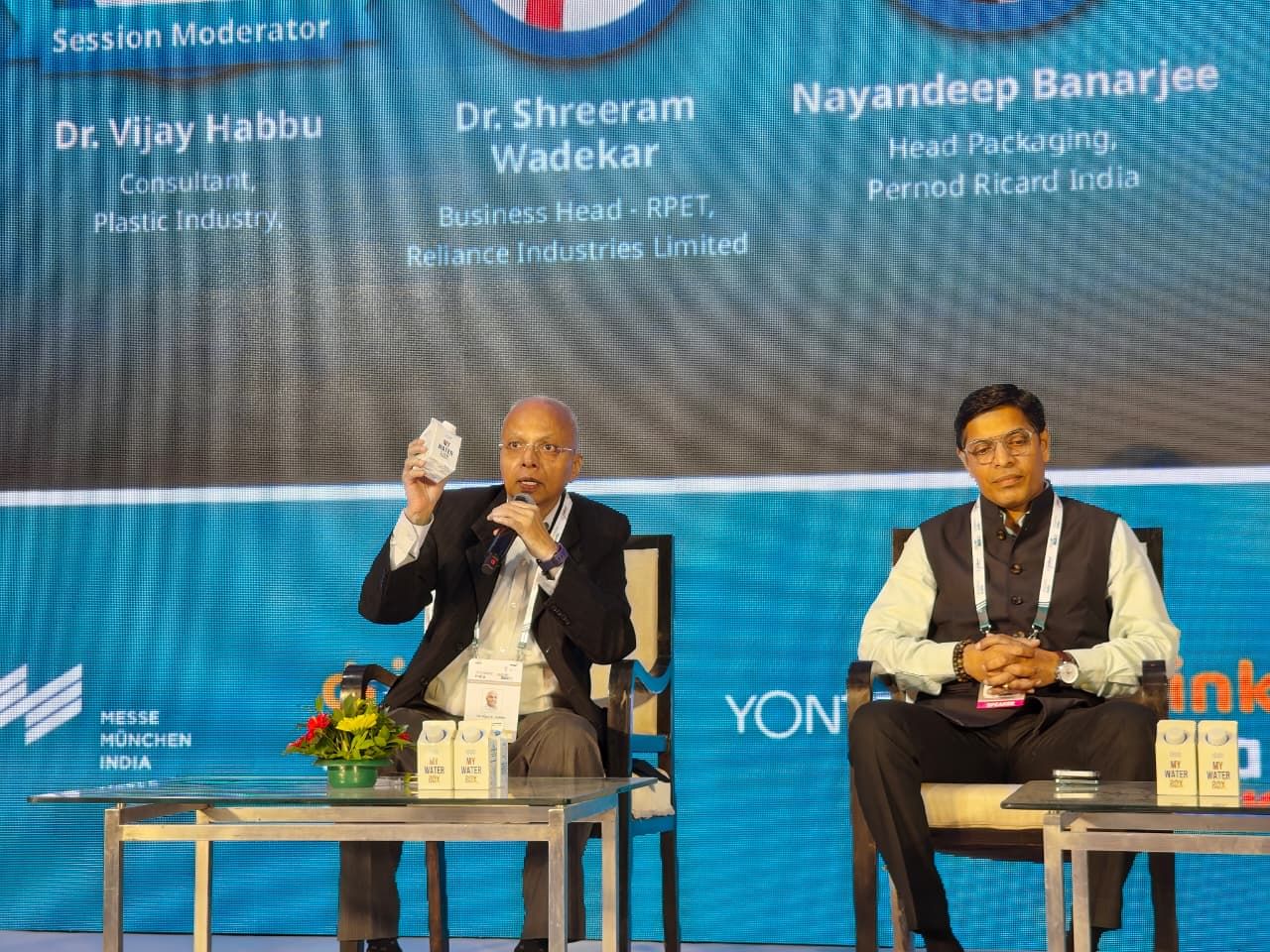

“Sustainability is as ubiquitous as income tax,” moderator Dr Vijay Habbu remarked as he opened the panel discussion on bio-based PET, rPET and EPR in the beverage industry. His analogy reflected the current dilemma: the word is everywhere, yet its meaning shifts depending on who defines it. To frame the conversation, Dr Habbu asked each speaker to share what sustainability means within their organisation.

Defining sustainability

Dr Shreeram Wadekar, business head – rPET at Reliance Industries, called sustainability a balance between present needs and the responsibility owed to future generations. He highlighted environmental protection, economic resilience and social equity as equal pillars.

Nayandeep Banerjee, head of packaging at Pernod Ricard India, viewed sustainability as a continuous journey that begins at the design stage. “Our first step is always to reduce,” he said, highlighting optimisation of packaging volumes long before regulatory obligations come into play.

For Subhra Sankha Nandi, packaging head at Wipro Consumer Care, sustainability must include affordability. “If sustainability is not financially viable, then it is not sustainable,” he said, emphasising the need for solutions that balance cost with environmental intent. Packaging consultant Dr Chakraborty framed sustainability as fitness for purpose, environmental, legal, industrial or functional.

From definitions, the session moved into the complexities underpinning sustainable packaging claims. Habbu displayed a gable-top carton marketed as a “smart choice”, using it to illustrate “greenwashing”. Though marketed as paper, such cartons contain aluminium layers and multiple plastics, he noted, making them more complex and expensive to recycle than a single-material PET bottle. This, he said, highlights the confusion and misdirection often inherent in sustainability debates.

Beyond mechanical recycling

Dr Wadekar outlined global trends in recycling, noting a clear shift towards advanced recycling, especially for hard-to-recycle multilayers and polymer composites used in automotive and electronics. Mechanical recycling for rigid PET and PE is mature, but emerging technologies including molecular depolymerisation and composite separation — are gaining traction in Europe, the US and Asia-Pacific. South Korea and Japan are leading in patent activity, with nearly 800 patents filed in a recent year. India too is seeing early-stage work on flexible packaging and textile waste recycling.

Glass vs PET

Banerjee detailed how Pernod Ricard is applying design-for-circularity principles across its portfolio. Nearly 60% of its glass bottles are sourced through a structured market-bottle return system, where collected bottles undergo multiple stages of inspection, washing and reuse. New developments such as wash-off label technologies, designed to detach within three minutes, are helping improve line efficiencies.

The company is also moving to smaller packs to PET while increasing recycled content to 30, 50 and even 100% rPET. Banerjee added that Pernod is exploring using the same market-bottle infrastructure to collect PET bottles in future.

Responding to a question on whether the successful glass-bottle return system can be replicated for PET, Dr Wadekar noted that several initiatives, such as incentivised collection models and brand-led take-back programmes—are underway. However, behavioural change across India’s vast consumer base will take time. Banerjee added that blockchain-based traceability and structured logistics could support such efforts, but cost and lifecycle analysis must justify the model.

Balancing sustainability with manufacturing realities

Nandi spoke of the complexities faced by FMCG manufacturers when shifting to sustainable packaging. For example, Wipro’s flagship Santur soap continues to use long-standing paper-poly wrappers because the company’s high-speed wrapping lines are calibrated for those substrates. “A simple shift to BOPP/BOPP drastically reduces machine speed,” he said. The interplay of capex, yield loss and sustainability commitments creates real-world constraints.

Wipro is actively pursuing downgauging and PCR incorporation across bottles but faces challenges such as colour variation, odour issues and consumer perception related to stiffness. “We are learning every day,” he said, adding that nitrogen flushing is being explored to improve bottle rigidity at lower weights.

Material innovations and the limitations of compostables

Dr Chakraborty discussed global efforts to improve barrier performance in single-material systems. EVOH continues to be the leading polymer for oxygen barrier coatings, while PLA and PBAT – though promising – do not deliver adequate barrier properties on their own. Coatings from companies like Toyo Ink are emerging as solutions for paper-based formats.

Banerjee offered a candid view of compostable materials, having developed Maggi’s compostable noodle cups earlier. Industrial composting requires strict temperature and humidity conditions but India lacks the infrastructure. Home compostables risk encouraging littering and, when disposed of in waterbodies, consume oxygen and damage ecosystems. He stressed that recycling systems, when properly implemented, remain far more beneficial from a life-cycle perspective.

Regulation, EPR and the limits of circularity

Wipro has a dedicated team handling EPR and regulatory compliance, ensuring alignment with government requirements. However, Nandi noted that compliance does not always translate to circularity: “I may meet my EPR targets, but my bottle is still lying in the street.”

Dr Chakraborty provided context on India’s regulatory evolution—from early plastic waste rules to the comprehensive 2016 framework and the current EPR guidelines. He highlighted that unlike Europe, which focuses heavily on reduction, India’s regulatory approach prioritises recycling to protect employment in its predominantly MSME-led plastics sector. He argued that India must urgently improve collection and segregation systems, as dependency on informal waste pickers limits the quality and reliability of recycled feedstock.

Conclusion

As the discussion closed, one theme stood out: no single organisation can solve sustainability alone. Collaboration will determine whether India can truly create circular packaging systems. The panel agreed that the coming decade will be critical as India balances regulatory pressure, material innovation, economic feasibility and the realities of consumer behaviour. Sustainability, ultimately, is not a destination but a shared journey grounded in practicality and continuous learning.